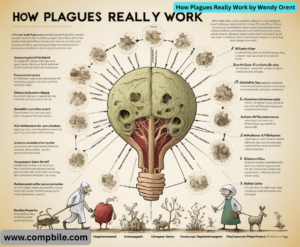

How Plagues Really Work by Wendy Orent Of course. Wendy Orent’s central argument in “How Plagues Really Work” is a direct challenge to the popular. simplified narrative of disease emergence. Here is a breakdown of her key thesis and the main points she uses to support it.

The Core Thesis: It’s Not Just “Spillover”

- The conventional story is that a new plague (like a pandemic virus) emerges when a pathogen simply “spills over” from an animal population into humans, and if it’s contagious enough, it spreads like wildfire.

- Orent argues this is dangerously incomplete. A pathogen doesn’t just jump and succeed. It must undergo a complex process of adaptation to its new human host to become a truly successful, widespread plague. The real story is one of evolutionary arms races and host-pathogen adaptation.

Key Arguments and Concepts

The Myth of the “Killer Bug”

- How Plagues Really Work by Wendy Orent Orent pushes back against the terrifying but simplistic idea of a “superbug” that emerges perfectly lethal and perfectly transmissible. In reality, there is often a trade-off between virulence (how sick it makes you) and transmissibility.

- A pathogen that kills its host too quickly may not have time to spread.

- The most successful plagues are those that strike a balance—they make you sick enough to spread it (through coughing, diarrhea, or contact) but not so sick that you immediately die or are completely isolated.

The Crucial Role of Adaptation

This is the heart of her argument. For an animal pathogen to become a human plague, it must evolve specific adaptations for human-to-human transmission. This involves:

- Binding to Human Cells: The virus or bacteria must evolve the ability to effectively latch onto human cell receptors (e.g., the way the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein binds to the ACE2 receptor).

- Evading the Human Immune System: It must develop mechanisms to at least partially circumvent our innate immune defenses.

- Finding an Efficient Exit Route: It must adapt to be shed in a way that facilitates spread—through the respiratory system, feces, blood, etc.

- This adaptation process isn’t instantaneous. It can happen through repeated small outbreaks that act as training grounds for the pathogen.

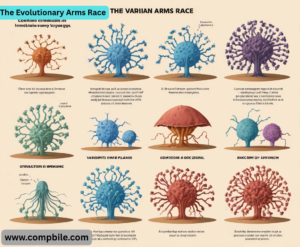

The Evolutionary Arms Race

- Orent emphasizes that plagues are not static. Once a pathogen establishes itself in a human population, it enters a continuous evolutionary dance with us.

- Host Immunity Drives Pathogen Evolution: As a population develops immunity (either through infection or vaccination), this puts selective pressure on the pathogen. Variants that can partially escape this immunity (like new COVID-19 variants) have a competitive advantage and become dominant.

- The Result: We don’t have a single “plague,” but a constantly shifting landscape of variants. The plague that ends a pandemic is often evolutionarily different from the one that started it.

Historical Examples to Support the Thesis

Orent uses history to illustrate her points:

- The Black Death (Yersinia pestis): She argues it wasn’t just a sudden, inexplicable catastrophe. The bacterium likely adapted and found the perfect conditions for spread—human fleas and body lice in densely populated, unsanitary medieval cities—turning a rodent disease into a human-specific nightmare.

- Smallpox: This is a prime example of a virus that became exquisitely adapted to humans alone. It had no animal reservoir and was perfectly tuned for human-to-human transmission, making it a devastatingly efficient plague for centuries.

- Influenza: The flu virus is a classic case of the ongoing arms race. Its constant mutation (antigenic drift) and occasional major shifts (antigenic shift) are why we need new vaccines regularly.

The Role of Social and Environmental Factors

- How Plagues Really Work by Wendy Orent While the biology of adaptation is central, Orent does not ignore context. She stresses that human behavior creates the opportunities for plagues.

- War, Famine, and Social Collapse: These conditions break down sanitation, displace populations, and weaken immune systems, creating the perfect breeding ground for pathogens to adapt and spread.

- Urbanization and Density: Dense populations provide the fuel for a newly adapted pathogen to become an epidemic.

- Ecological Disruption: Deforestation and live animal markets (wet markets) increase the points of contact between humans and wild animal reservoirs, providing the initial “spillover” opportunities that can kickstart the adaptation process.

Conclusion and Implications

- Wendy Orent’s model, therefore, is not one of random catastrophe but of predictable evolutionary processes.

The practical implications of her view are significant:

- Surveillance is Key: We shouldn’t just look for “the big one.” We need to monitor small, contained outbreaks, as these are the potential crucibles where pathogens are adapting.

- Focus on Adaptation, Not Just Spillover: Understanding the molecular and evolutionary steps a pathogen takes to become efficient in humans is crucial for developing countermeasures.

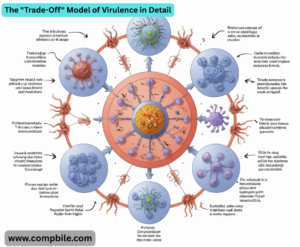

- A More Nuanced View of Virulence: A pathogen’s deadliness isn’t a fixed trait; it’s a dynamic outcome of its evolutionary relationship with its host.

The “Ghost of Plagues Past”: The Attenuation Theory

- How Plagues Really Work by Wendy Orent One of Orent’s most compelling arguments is that highly lethal plagues often attenuate (become milder) over time. This isn’t guaranteed, but it’s a common evolutionary trajectory.

- Why? A pathogen that kills almost all its hosts is a evolutionary dead end. It burns through its fuel supply too quickly.

- The Historical Pattern: The initial outbreak is often the most virulent. As the plague cycles through a population, strains that allow the host to live longer, move around, and interact with others—even while sick—are the ones that get passed on.

- Example: The “Plague of Justinian” vs. later Bubonic Plague outbreaks. Some historians and scientists argue that the initial wave of a new plague is often the most severe, and subsequent waves or related diseases may be less virulent, as the pathogen and host population co-evolve toward a less lethal, more stable relationship.

The Critical Difference Between “Disease” and “Plague”

Orent makes a crucial distinction that is often lost in public discourse:

- A Disease: A health condition that can be caused by a pathogen. It can be sporadic, localized, or chronic (e.g., Lyme disease, foodborne E. coli).

- A Plague: A disease that has become a widespread, catastrophic social and demographic event. It requires efficient human-to-human transmission and the right social conditions to explode.

- A pathogen can cause a disease without ever causing a plague. For Orent, the transition from one to the other is the key event, and it hinges on the adaptation process.

The “Trade-Off” Model of Virulence in Detail

- This is a central concept in evolutionary medicine that Orent champions. The idea is that virulence is not a random mistake; it is often a byproduct of the pathogen’s method of transmission.

High Virulence is “Tolerated” when Transmission Depends on It:

- How Plagues Really Work by Wendy Orent Example: Cholera. The bacterium (Vibrio cholerae) causes massive, watery diarrhea. This is terribly debilitating for the host (high virulence), but it is also the very mechanism that contaminates water supplies and spreads the pathogen to new hosts. It can’t afford to be mild.

- Example: The Common Cold. This virus has very low virulence. It doesn’t need to make you very sick to spread; a simple sneeze or a touch on a doorknob is sufficient. It thrives on high transmissibility and low impact.

- What about Diseases like Rabies? Rabies is a fascinating exception that proves the rule. It is almost 100% fatal and has no real human-to-human transmission. It is a “dead-end” infection in humans. Its survival strategy relies on altering the host’s behavior (aggression, hydrophobia) to ensure it is transmitted via bites back to its animal reservoir, where it circulates effectively. It is not a human plague; it’s a zoonotic disease.

The Role of Globalization and Modernity

Orent’s framework explains why modern times, despite our medical advances, are more, not less, vulnerable to plagues.

- The “Adaptation Lab”: In the past, a pathogen might emerge in a remote village, adapt somewhat, and then burn out locally. Today, a single infected person can get on a plane and transport a partially adapted pathogen to a major global hub within hours, providing it with a planet-sized adaptation lab.

- Speed Overwhelms Evolution: The speed of modern travel means a pathogen can spread globally before it has fully optimized its human-to-human transmission. This is what likely happened with SARS-CoV-2—it was already quite transmissible when it was first detected, and it continued to adapt (see Alpha, Delta, Omicron) after it had already become a pandemic.

Case Study: Applying Orent’s Lens to COVID-19

Viewing the COVID-19 pandemic through Orent’s ideas is illuminating:

- Spillover: The virus (SARS-CoV-2) likely originated in bats and spilled over into humans, possibly through an intermediate host.

- Initial Adaptation: It clearly had already achieved a significant level of adaptation for human ACE2 receptors, allowing for efficient transmission even before it was identified.

- The Arms Race in Real-Time: The emergence of variants (Alpha, Delta, Omicron) was a textbook example of the evolutionary arms race Orent describes.

- Delta: Evolved for higher viral loads and better replication, increasing transmissibility and virulence.

- Omicron: Evolved for immune evasion, allowing it to infect vaccinated or previously infected people, and shifted its replication to the upper airways, making it even more transmissible (though often less severe for many individuals—a potential step in attenuation).

- Social Factors: Dense cities, international travel, and superspreader events provided the perfect tinder for the adapted virus to become a global plague.