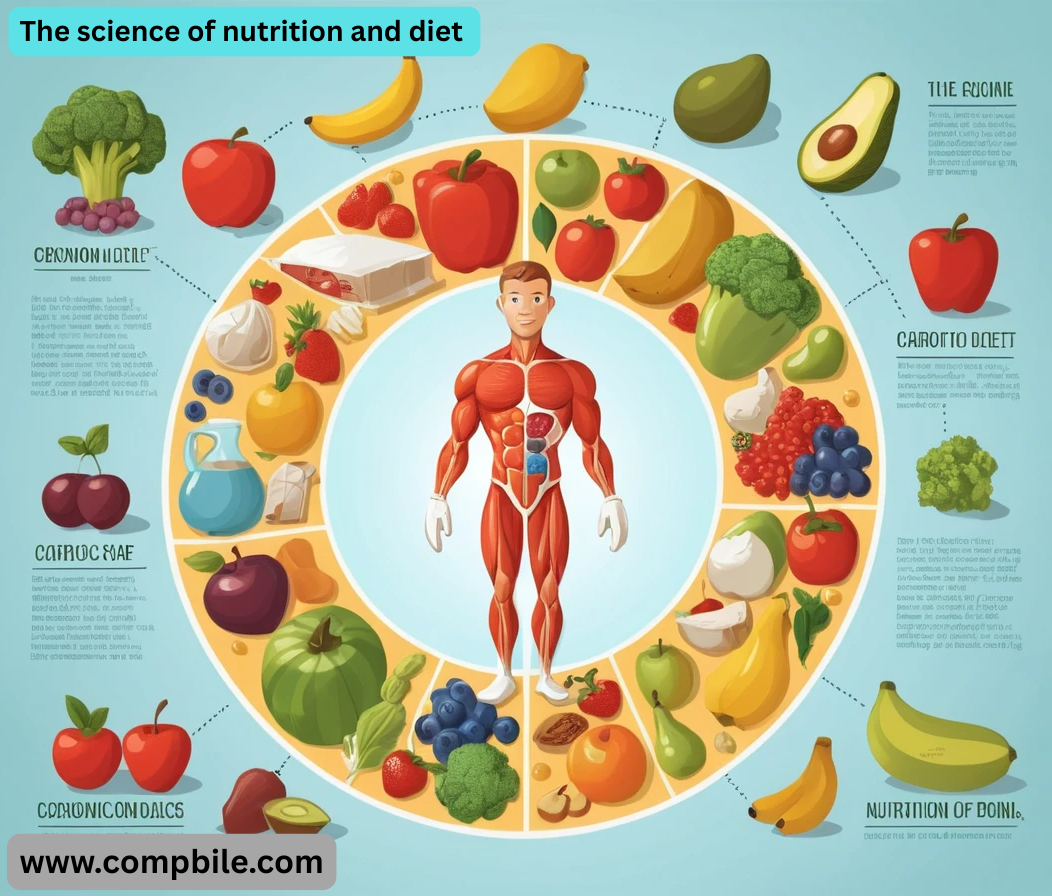

The science of nutrition and diet Of course. The science of nutrition and diet is a vast, dynamic, and fascinating field that explores the complex relationship between the food we consume and our health, well-being, and risk of disease. It’s an interdisciplinary science, drawing from biochemistry, physiology, medicine, psychology, and public health. Here is a comprehensive breakdown of its core components, principles, and current debates.

Core Macronutrients: The Building Blocks

These are nutrients the body needs in large amounts to produce energy and maintain structure and systems.

- Carbohydrates: The body’s primary source of energy.

- Simple Carbs: Sugars (e.g., glucose, fructose, sucrose) found in fruits, milk, and processed foods. They provide quick energy.

- They provide sustained energy and are crucial for digestive health.

- Function: Fuel for the brain and muscles, digestive health (fiber).

- Incomplete Proteins: Lack one or more essential amino acids (e.g., beans, nuts, grains). These can be combined to form complete proteins.

- Function: Build and repair tissues, make enzymes and hormones, support immune function.

- Fats: Essential for numerous bodily functions, often misunderstood.

- Saturated Fats: Found primarily in animal products (meat, dairy). Should be consumed in moderation.

- Function: Energy storage, hormone production, absorption of fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E, K), insulation.

Essential Micronutrients: The Vital Helpers

Needed in smaller quantities but are critical for thousands of physiological processes.

- Vitamins: Organic compounds.

- Water-Soluble: Vitamin C and B-complex vitamins.

- Function: Support immunity (Vit C), vision (Vit A), bone health (Vit D), blood clotting (Vit K), and energy production (B vitamins).

- Minerals: Inorganic elements.

- Macrominerals: Needed in larger amounts (e.g., calcium, potassium, magnesium, sodium).

- Trace Minerals: Needed in tiny amounts (e.g., iron, zinc, selenium, iodine).

- Function: Bone structure (calcium), oxygen transport (iron), fluid balance (sodium, potassium), thyroid function (iodine).

Key Principles of a Healthy Diet

Based on decades of research, most major health organizations agree on these principles:

- Adequacy: Providing all the essential nutrients, fiber, and energy necessary to maintain health.

- Calorie Awareness: Understanding that weight management is primarily about energy balance (calories in vs. calories out), though the quality of those calories is paramount for health.

- Moderation: Not eliminating any food group entirely (unless for medical reasons) but managing portion sizes, especially for foods high in added sugar, sodium, and unhealthy fats.

Debates and Evolving Areas in Nutritional Science

This is where the field gets interesting and sometimes contentious. Science is always evolving.

- Low-Carb (Keto) vs. Low-Fat: Which is better for weight loss and health? Current evidence suggests that diet quality is more important than macronutrient quantity. A healthy low-carb diet (rich in vegetables) can work, as can a healthy low-fat diet (rich in whole grains and legumes). The worst diet is one high in ultra-processed foods, regardless of its carb/fat ratio.

- The science of nutrition and diet The Role of Ultra-Processed Foods: A major area of current research. Studies consistently link high consumption of ultra-processed foods (e.g., sugary drinks, packaged snacks, reconstituted meats) to obesity, heart disease, and earlier death, even if they are marketed as “low-fat” or “high-protein.”

- Personalized Nutrition (Nutrigenomics): The idea that there is no one-size-fits-all “perfect diet.” Our genes, gut microbiome, metabolism, and lifestyle can influence how we respond to different foods. This is the future of nutrition science.

- Sustainability and Ethics: Nutrition is increasingly viewed through an environmental lens. Diets lower in animal products (e.g., Mediterranean, vegetarian, vegan) are often promoted for both health and environmental sustainability.

How to Apply This Science: Evidence-Based Advice

Cutting through the noise and fad diets, here is the consensus from global health authorities:

- Prioritize healthy protein sources like legumes, nuts, fish, and poultry. Limit red and processed meats.

- Use healthy fats from plants (olive oil, avocados, nuts) for cooking and flavor.

- Limit added sugars, sugary drinks, and excessive sodium.

- Stay hydrated with water.

Important Disclaimer

Nutrition science is complex because it’s difficult to conduct perfect long-term dietary studies on humans. It relies on a combination of:

- Epidemiological Studies: Observing large populations to find correlations between diet and health.

- Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs): The gold standard for testing specific interventions.

- Basic Science: Understanding the biochemical mechanisms of nutrients in the body.

- The strongest recommendations are based on a consensus of evidence from all these types of studies.

The Gut Microbiome: The Internal Ecosystem

- The science of nutrition and diet This is one of the most exciting frontiers in nutritional science. The gut microbiome refers to the trillions of bacteria, viruses, and fungi living in our digestive tract, primarily the colon.

- Function: This community is not passive; it’s an active “organ” that:

- Ferments dietary fiber we can’t digest, producing short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) that are crucial for colon health and reduce inflammation.

Synthesizes certain vitamins (B vitamins and Vitamin K).

Plays a fundamental role in training and regulating our immune system (70-80% of which resides in the gut).

- Influences brain health and mood via the gut-brain axis.

- Nutritional Impact: Diet is the primary driver of the microbiome’s composition.

- Prebiotics: These are food for beneficial bacteria. They are types of fiber found in foods like garlic, onions, leeks, asparagus, bananas, and oats.

- Probiotics: These are live bacteria themselves, found in fermented foods like yogurt, kefir, kimchi, sauerkraut, and kombucha. They can temporarily introduce beneficial strains.

- The Goal: A diverse diet rich in various fibers leads to a diverse microbiome, which is strongly associated with better health outcomes.

The Physiology of Weight Regulation: It’s More Than “Eat Less, Move More”

While energy balance (calories in vs. calories out) is a fundamental law of physics, the physiological experience of regulating weight is complex and involves powerful biological feedback loops.

- Hormonal Regulation: Key hormones dictate hunger and satiety (fullness).

- Ghrelin: The “hunger hormone” secreted by the stomach.

- Leptin: The “satiety hormone” secreted by fat cells. It signals to the brain that you have sufficient energy stores.

- It also promotes fat storage and can influence hunger signals.

- Metabolic Adaptation: When you lose weight, your body defends its former, higher weight (“set point theory”).

- Metabolism Slows: Your body burns fewer calories at rest (decreased Resting Energy Expenditure).

- Hunger Increases: Levels of ghrelin rise, and leptin falls, making you feel hungrier and less full.

- This is a primary reason why long-term weight loss is so challenging—it’s a battle against biology, not just willpower.

Critical Analysis: How to Spot Bad Nutrition Science

The field is flooded with misinformation. Here’s how to be a critical consumer:

- The science of nutrition and diet Beware of “Miracle Food” or “Superfood” Claims: No single food can make you healthy or cure disease. Health is built on dietary patterns.

- Question Sensationalist Headlines: They often misrepresent the findings of a study. Always read beyond the headline.

- Look at the Study Type: Is it a cell or animal study? These are preliminary. A human randomized controlled trial (RCT) is more powerful than an observational study (which can only show correlation, not causation).

- Check for Conflict of Interest: Was the study funded by a company that would benefit from a specific result?

- Consider the Scope: Was the study done on 10 people for a week, or 10,000 people for a decade? Larger, longer studies are more reliable.

- The “Who” Matters: Recommendations from a celebrity influencer are not the same as those from a Registered Dietitian (RD) or Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) in nutritional science, who are trained to interpret research.

Emerging Concepts and Hot Topics

- Chrononutrition / Time-Restricted Eating (TRE): This explores when we eat, not just what we eat. The most popular form is intermittent fasting (e.g., 16:8 method). Early research suggests benefits for metabolic health by aligning eating patterns with our circadian rhythms.

- Personalized Nutrition: The concept that there is no single “best” diet for everyone. Our unique genetic makeup, microbiome, metabolism, and lifestyle mean we can have different responses to the same foods. (e.g., Glycemic response to a banana can vary dramatically between individuals).

- Food and Mental Health (Nutritional Psychiatry): A growing field investigating how diet quality impacts mental health conditions like depression and anxiety.

- Non-Nutritive Sweeteners (NNS): The debate continues. While they are generally recognized as safe for consumption by regulatory bodies, emerging research is questioning their long-term effects on the gut microbiome, glucose metabolism, and appetite regulation. The science is not yet settled.

- Putting It All Together: The Anti-Inflammatory Dietary Pattern

Modern nutritional science is moving away from isolated nutrients and towards overall dietary patterns. One of the most evidence-based patterns is the Anti-Inflammatory Diet, which is very similar to the Mediterranean, DASH, and MIND diets. - Its goal is to reduce chronic, low-grade inflammation—a root cause of many modern diseases (heart disease, diabetes, cancer, Alzheimer’s).